Development and evaluation of a pediatric nursing competency-building program for nursing students in South Korea: a quasi-experimental study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The present study aimed to develop and examine the effectiveness of a pediatric nursing competency-building program for nursing students.

Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with a nonequivalent control group pretest-posttest design conducted between October and December 2021. The participants included 40 nursing students (20 each in the experimental and control groups) at a university in a South Korean city. The pediatric nursing competency-building program integrated problem-based learning and simulation into clinical field practice. The experimental group participated in the program, while the control group did not. Data were analyzed using the x2 test, the independent t-test, and repeated-measures analysis of variance.

Results

Pediatric nursing competency and clinical performance showed a greater increase in the experimental group than in the control group. However, the change in problem-solving ability in the experimental group was not significantly different from that in the control group.

Conclusion

The pediatric nursing competency-building program effectively improved students' pediatric nursing competency and clinical performance.

INTRODUCTION

Nursing students learn nursing and health assessment skills to improve patient health, and nursing processes for aiding children's recovery through pediatric nursing theories and practicums [1]. Compared to adults, children's physical functions are underdeveloped, placing children at high risk of negative outcomes from infections and injuries. Therefore, accurate and meticulous nursing care must be provided to child patients while education and support are offered to the parents and family members who act as caregivers for pediatric patients [2]. Nursing students must develop sufficient competency through education to be able to identify and resolve nursing problems related to pediatric patients and their families, thereby promoting the health recovery of children and their families, as nurses in clinical settings after graduation [3].

In recent years, nurses in clinical practice have faced a high volume of work due to outbreaks of novel infectious diseases, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and the increasing severity of cases among children. At the same time, however, to prevent the further spread of infection, nursing students are only allowed limited clinical practice opportunities [4]. It is increasingly difficult for students to directly perform nursing duties for children, who are vulnerable to diseases and infections [5]. Nurses who provide instruction in clinical settings also feel limited since students often can only observe due to legal and ethical issues that prevent them from engaging in direct nursing practice [6]. In the pediatric ward environment, students want to observe child nursing work with explanations from nurses, and at the same time, both nurses and students need to experience care for children directly through in-school practice [5].

To address these challenges related to nursing education, various educational methods such as problem-based learning (PBL) and simulation have been implemented, and many changes to the nursing education system have been attempted [7-9]. PBL is a learning method in which students address real-world problems in small groups by collecting information, reconstructing knowledge, and resolving issues independently [10]. In a previous study [9], the self-learning and problem-solving abilities of nursing students who participated in a PBL program for pediatric nursing improved compared to those who did not participate in the program. In addition, simulation programs have been developed and implemented in nursing practicums so that students can develop nursing skills in controlled and safe environments [7,11,12]. Simulation, which is a method for repeated learning, recreates real-life scenarios that students have not yet experienced in clinical practice [13]. Nursing students who participated in simulations were found to have improved learning outcomes [14] and found education through simulation to be an engaging process [15].

Research has been conducted to develop and implement PBL and simulation programs to help nursing students reach educational goals that cannot be achieved in clinical practice; however, most studies have examined the efficacy of PBL and simulation as independent programs separate from nursing practicums [7,16-19]. To foster pediatric nursing competency, practicums are essential for students to apply the nursing knowledge and skills they have acquired in the actual clinical field. Therefore, to enhance students' pediatric nursing competency, PBL and simulations should be incorporated in practicums rather than operated as independent programs.

Thus, this study aimed to develop a pediatric nursing competency-building program that incorporates PBL and simulation as well as clinical field practice for nursing students and to evaluate the program's effectiveness. The purpose of this educational program was to strengthen the nursing capability of nursing students, and the present study therefore aimed to measure the effectiveness of this program. The following hypotheses were examined in this study. First, pediatric nursing competency would show a greater increase in the experimental group than in the control group. Second, clinical performance would show a greater increase in the experimental group than in the control group. Third, students' problem-solving ability would show a greater increase in the experimental group than in the control group.

METHODS

Ethics statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Daegu Catholic University (No. CUIRB-2021-0070). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

1. Research Design

This was a quasi-experimental study with a nonequivalent control group pretest-posttest design (Figure 1). This study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) reporting guidelines [20].

2. Participants and Setting

Convenience sampling of students at a nursing college in Daegu in South Korea was conducted from October to December 2021. The inclusion criterion was third-year students who were in the course of earning 1 credit (45 hours) from pediatric nursing practicums. Only those who provided written voluntary consent to participate in the study were included, and those who did not agree to participate or did not attend a pediatric nursing practicum were excluded. The required number of participants was 17 students per group, which was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.7 [21]. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a within-between interaction were applied, with an effect size of .25, a significance level of .05, a power of 80%, a correlation coefficient of .50, and a number of measurements of 2. The effect size was set to .25, which was the median size based on a previous study [16]. Given a possible dropout rate of 15%, a total of 40 students were assigned to the experimental and control groups (20 students in each group), all of whom were included in the final analysis without any dropouts. Students were divided into six teams, and one team per week participated in the practice. The three teams participating in the first half of the practice were assigned to the experimental group and the three teams participating in the second half of the practice were assigned to the control group.

3. Development of the Pediatric Nursing Competency-Building Program

The analysis, design, development, implementation, evaluation (ADDIE) model [22] was used to develop the program.

In the analysis phase, five clinical practice faculty members (CPFs), five clinical nursing instructors (CNIs), and five nurses were surveyed and interviewed to identify students' learning needs and demands in the field. In addition, based on a review of learning goals in pediatric nursing [1] and the literature on pediatric nursing practice education and guidance [12,23,24], we analyzed the educational goals and methods used in pediatric nursing practicums to strengthen students' pediatric nursing competency. As a result, the following elements were incorporated in the program: observation and monitoring of children's conditions, communication and rapport formation with children and their caregivers, parent education, administering medication, oxygen therapy, fever management, and emergency response. In addition, PBL and simulation were included as educational methods in the program.

In the design phase, we created scenarios and designed a program that incorporated simulated practice scenarios and PBL. According to the needs analysis, the theme of the simulation scenario was selected as febrile seizure, an emergency situation related to fever. The scenario was designed for participants to find nursing problems in children experiencing febrile seizures, cope with the situation, and solve the problems. It was also designed to involve communication with parents in the situation of a febrile seizure and education for parents on how to cope with febrile seizures.

In the development phase, we developed a pediatric nursing competency-building program in which nursing students participated in simulations to learn about febrile seizures and applied PBL using actual clinical cases for 5 days during a pediatric nursing practicum.

In the implementation phase, 2 days before a practicum, trainees were given a pre-learning assignment to complete that consisted of a worksheet on febrile seizures, parent education, administering medication, and oxygen therapy. In the practicum, six or seven students were divided into small groups of three to four and performed small-group activities. On the first day of the practicum, the trainees received an orientation from a CPF, and each small group was given a task to assess the nursing problems of a hospitalized child. On the second day, the trainees participated in group study for 1 hour, during which they presented and discussed the contents of the pre-learning worksheets they had completed, so the students would have sufficient knowledge about febrile seizures. On the third day, the trainees participated in a 4-hour simulation to practice treating febrile seizures, which consisted of pre-briefing, situation analysis, nursing skills practice, simulation, and a debriefing. One of the researchers conducted the group study and simulation. On the fifth day, each small group briefly presented the results of their assessment of the nursing problems of a hospitalized child, which was completed independently, and PBL was conducted for 3 hours on a case that was selected. The CPF acted as the facilitator of the PBL portion and encouraged students to resolve nursing problems observed from actual cases on their own and while they studied nursing.

The validity of the composition and content of the program was verified by two CPFs, two CNIs, and two nurses, and the program was considered completed after all reviewers responded that the contents were appropriate or very suitable (Table 1).

4. Implementation and Evaluation of the Pediatric Nursing Competency-Building Program

To prevent the spread of the experimental effect and ensure blinding, the participants and CPFs were not informed about the assignment completed by the experimental and control groups. Since teams in the clinical practice department (6 to 7 people per team) switched every week (from Monday to Friday for a total of 5 days) according to the practicum schedule, students who practiced in the pediatric ward during the first half of the study period were assigned to the experimental group, and the students who practiced in the pediatric ward in the second half of the study period were assigned to the control group. In accordance with clinical practice operation regulations, the same practice location, practice time, and practice guidelines were applied for both groups.

The participants responded to the pretest survey 2 days before the start of the practicum in the pediatric ward. One researcher and the CPF conducted the program in the experimental group with a team of 6 or 7 people. In the control group, the students were asked to prepare and present individual reflection reports and case reports instead of participating in simulations and PBL. The participants responded to the posttest survey within 2 days of the completion of their pediatric ward experience. The participants were asked to submit a self-reported online questionnaire to ensure blinding. Since the participants were not allowed to proceed with the survey if there were unanswered questions, no data were missing for the analysis. After completion of the posttest survey, the same simulation included in the program was conducted with those in the control group.

5. Instruments

All tools were designed as self-reported online questionnaires using NAVER Form, and permission was obtained from the original authors of the tools.

1) Pediatric nursing competency

Pediatric nursing competency was assessed using a tool developed by the researchers based on the pediatric nursing learning objectives [1]. Seven items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 point=not at all; 5 points=strongly agree), and a higher score indicated a higher level of pediatric nursing competency. An example of an item is: I can conduct a nursing assessment by collecting a child's nursing history and evaluating his or her growth and development. Cronbach's α, as an indicator of internal reliability, was .91 in the pretest and .86 in the posttest.

2) Clinical performance

Clinical performance was assessed using the tool developed by Yang and Park [25]. A total of 19 items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 point=strongly disagree; 5 points=strongly agree), and a higher score indicated higher clinical performance. An example of an item is: I can safely administer the medication in the correct way. In the study of Yang and Park [25], Cronbach's α was .86, and, in the current study, it was .94 in both the pretest and posttest assessments.

3) Problem-solving ability

Problem-solving ability was assessed using a tool developed by Lee et al. [26]. A total of 30 items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 point=rarely; 5 points=very often), and a higher score indicated higher problem-solving ability. An example of an item is: I choose a solution to the problem based on scientific evidence. In the study by Lee et al. [26], Cronbach's α was .93. In the current study, Cronbach's α was .96 in the pretest and .97 in the posttest.

6. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The pre-intervention homogeneity of the experimental and control groups was tested using the x2 test and the independent t-test. Differences in pediatric nursing competency, clinical performance, and problem-solving ability according to the intervention were tested

7. Ethical Considerations

To ensure the ethical protection of the participants, this study was conducted after obtaining approval from the IRB of Daegu University (CUIRB-2021-0070). The research purpose, methods, procedures, confidentiality, anonymity, and the data handling procedures after completion of the study were explained to all prospective participants. In addition, potential participants were informed that there would be no penalty for declining to participate or withdrawing from the study and that participation in the study had no effect on course credits. Those who provided written informed consent to voluntarily participate in the study were selected as the study participants. The data collected through the online survey were downloaded as an Excel file after the data collection was completed, and then were deleted from the online drive. The downloaded data were stored on the researcher's personal computer with a password and used for data analysis, and the data will be stored for 3 years and discarded. After participating in the study, coffee vouchers were given to students.

RESULTS

1. Participants' Characteristics

There were no significant differences between the experimental group and the control group in general characteristics, including age, gender, academic achievement, health status, and satisfaction with school life. There was no significant difference in pediatric nursing competency between the groups, but the clinical performance and problem-solving ability of those in the control group were significantly higher than those in the experimental group (Table 2).

2. The Effects of the Pediatric Nursing Competency-Building Program

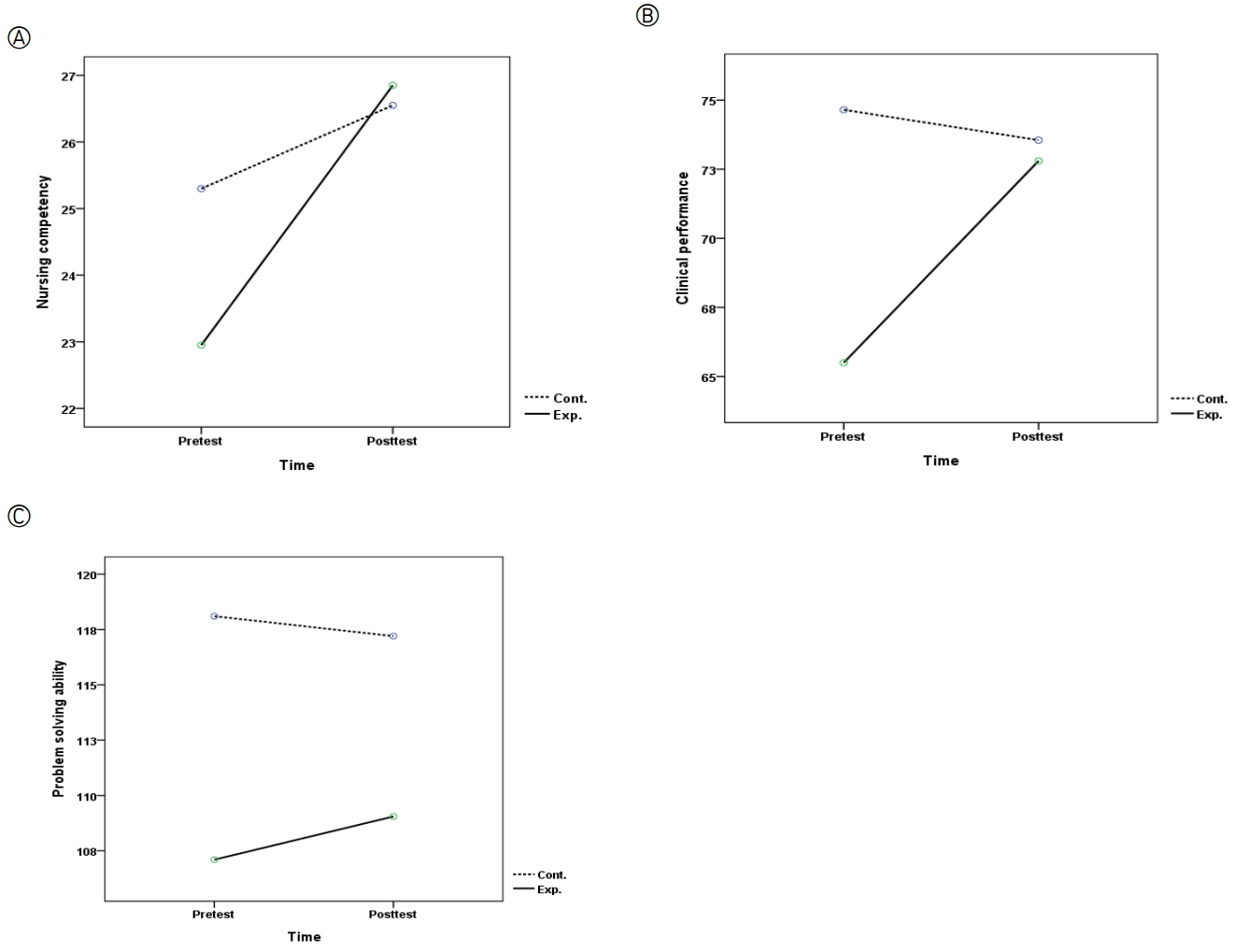

Pediatric nursing competency showed a significant difference according to time between the groups (F=6.24, p=.017). There was a significant difference between time points (F=23.57, p<.001); however, there was no difference between the groups (F=0.80, p=.377). That is, the patterns of change after the intervention were significantly different between the experimental group and the control group. Pediatric nursing competency showed greater improvement in the experimental group than in the control group, supporting our first hypothesis.

Clinical performance was significantly different between the groups according to time (F=12.65, p=.001). There was a difference between time points (F=6.89, p=.012); however, there was no difference between the groups (F=3.82, p=.058). Thus, the patterns of change after the intervention were significantly different between the experimental group and the control group. The finding that clinical performance showed greater improvement in the experimental group than in the control group supported our second hypothesis.

Problem-solving ability was not significantly different between the groups according to time (F=0.44, p=.509), and there was no difference between time points (F=0.06, p=.807) or between groups (F=3.76, p=.060). In other words, the pat-terns of change after the intervention were not significantly different between the experimental group and the control group, refuting hypothesis 3 (Table 3, Figure 2).

Pediatric Nursing Competency, Clinical Performance, and Problem-Solving Ability between the Groups (N=40)

DISCUSSION

In this study, pediatric nursing competency and clinical performance improved more significantly among students who participated in a pediatric nursing competency-building program that incorporated PBL and simulation into clinical field practice than students who did not. PBL facilitates self-directed learning in the process of solving unstructured real problems [10]. Therefore, we believe that the process of identifying and solving nursing problems in real scenarios allowed students to apply theoretical knowledge to actual pediatric patients, resulting in stimulated students' interest in learning and improved nursing competency and clinical performance. In addition, simulations allow students to practice nursing activities that are difficult to perform in the actual field through high-fidelity recreations with standardized patients in safe and controlled conditions [16]. Thus, we believe that practice using simulations for nursing children with febrile seizures was effective for improving nursing competency and clinical performance.

PBL and simulation were specifically integrated into a pediatric nursing practicum in our program, thereby enabling students to practice and vividly experience the application of their nursing knowledge in the actual clinical field. Most studies on PBL and simulation in nursing education examined their efficacy through standalone programs conducted apart from clinical practicum [7,16-19]. Since students develop the ability to care for patients through training courses in which they apply their theoretical knowledge of nursing in clinical settings [27], it is unrealistic to expect certain educational methods, despite their effectiveness, to fully replace clinical practicums. Clinical practicums provide an opportunity for students to improve their theoretical knowledge by learning nursing skills from experienced nursing professionals and facing various problems in a real-life setting [28]. Therefore, the method of integrating PBL and simulation into clinical practicums can be used to strengthen nursing students' pediatric nursing competency.

In this study, we created a simulated scenario by identifying the demands of the clinical field through a survey of various personnel, including CPFs, CNIs, and nurses, and conducted PBL on the subject of actual health issues experienced by hospitalized pediatric patients. We believe that this increased the students' interest, encouraged their active participation, and met their needs, resulting in improved nursing competency and clinical performance. To ensure a positive educational effect, examples should be presented that are suitable to the students' learning levels so they can succeed in problem-solving [29]. Students' vivid experiences in a real clinical setting can foster a strong connection to nursing knowledge and actual clinical work.

Through PBL and simulation, the students solved problems together during team activities. They talked about what they had studied in advance, and students incidentally shared knowledge among each other so that all team members participated actively and learned through a collaborative exchange. In a systematic review [30], team learning was found to have the advantage of increasing the level of academic achievement, and conducting PBL and simulations in the context of team activities can be effective for improving students' pediatric nursing competency.

In this study, clinical performance in the experimental group was lower than in the control group in the pretest, but it improved significantly after the intervention, whereas no notable difference was observed in the control group before and after the clinical practicum. To prevent the spread of the experimental effect, students who participated in the first half of the clinical practicum were assigned to the experimental group, and students who participated in the latter half of the clinical practicum were assigned to the control group. It is possible that the pretest clinical performance level was higher in the control group since they may have already experienced more hours of clinical practice than the experimental group. Given the significant increase in clinical performance among those in the experimental group after participating in the 5-day program, integrating PBL and simulation into a clinical practicum may be effective for rapidly improving students' clinical performance.

However, in the current study, the pattern of changes related to problem-solving ability did not differ between the experimental and control groups. Similar results were reported in previous studies [12,18] in which the problem-solving ability of nursing students who participated in simulation classes did not differ between the experimental and control groups. In contrast, in another previous study, the problem-solving ability of nursing students who participated in a pediatric nursing program incorporating PBL improved significantly compared to the control group [9]. In the simulation, we used a scenario that emphasized problem-solving [12] and considered the need to set a specific scenario that students would understand [18], but students' problem-solving ability still did not significantly improve. Problem-solving involves the process of clarifying a problem, exploring solutions, selecting the best solution, applying it, and making an evaluation [26]. Sufficient training is required to develop this ability. In the current study, the intervention period was 5 days, which is shorter than the 7-week period in a previous study [9]. Therefore, the period during which the program is conducted should be extended in future studies to confirm its effects.

In the control group, it was found that students' clinical performance and problem-solving ability were rather lower after clinical practice. As pediatric ward practice was conducted during the period of COVID-19 spread, it was impossible for students to come into close contact with children, and direct nursing was difficult due to the decrease in hospitalized children. It is presumed that the clinical performance and problem-solving ability of the control group students, who practiced other skills in adult wards, further decreased after pediatric ward practice. Therefore, it can be seen that it is necessary to apply various educational methods and strategies, such as simulations or PBL, to clinical practice in special circumstances such as COVID-19.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted with students enrolled at one nursing college through convenience sampling, and the groups were not homogeneous, so caution should be taken when interpreting and generalizing the study results. Second, the clinical practice experience differed between the groups as a result of assigning the study participants into the experimental and control groups according to their clinical training period to prevent the spread of the experimental effect and to ensure blinding. Future studies should be designed to effectively reduce the differences in experience levels between the participants. Third, in order to change students' problem-solving ability, it is necessary to consider the program period. Fourth, while the pretest and posttest were completed once by the students in each group, follow-up investigations should be conducted to verify the long-term effects of the program.

CONCLUSION

This study was conducted to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a pediatric nursing competency-building program for nursing students in South Korea. The program integrated PBL and simulation components into clinical field practice. The experimental group participated in a program in which groups of six to seven nursing students took part in simulations to learn about febrile seizures and applied PBL using actual clinical cases. The results indicated that the program effectively improved students' pediatric nursing competency and clinical performance. The pediatric nursing competency-building program can therefore continue to be implemented to improve the pediatric nursing competency of nursing students.

Notes

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization: Hyun Young Koo; Data collection, Formal analysis: all authors; Writing-original draft: Hyun Young Koo; Writing-review and editing: all authors; Final approval of published version: all authors.

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study was supported by the research fund of Daegu Catholic University in 2021.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgements

None.